Deutsche Cloud

Due to the unique political situation we are living in, there is an increased demand for European technology solutions. Call it derisking, sovereignty, or nationalism. Everybody seems to be at least pretending to look for new solutions from within.

The German IT industry is classically laggard: while the rest of the world is beginning to understand that the benefits of cloud computing are technological, not economic, in Germany, all the rage seems to be in public cloud these days. In my local government, everybody seems to have learned the word “hyperscaler” recently and doesn’t hesitate to repeat it relentlessly with limited understanding.1

When Microsoft builds a data center in Germany, everybody seems to ignore all the nasty details and declares it EU-cloud, congratulating themselves on getting the deal.

A particularly strange public sentiment I’ve encountered is the admiration of the Schwarz Group IT division “Schwarz Digits” and their brand “STACKIT”. The Schwarz Group is the holding company of one of the biggest retailers in Germany. In 2022, they entered the limelight by starting a public cloud offering that they built based on their own needs and opened to the general public. A retailer building their own IT services and selling them as a service? How 2002!

I don’t mind people taking affairs into their own hands and building their own thing: buy hardware to run your software on? Sounds great, I’m in! But if you look at it for more than a few seconds, the details are massively underwhelming.

The service palette itself is a little bit sparse: aside from quite low-level features like virtual machines and block storage, they claim to run a handful of databases and other managed services. They offer only one message queue and it’s RabbitMQ, an odd choice.

There is no transactional email service, and their workspace offering is just Google Workspace in a trench coat.

The underpinnings are based on OpenStack: a sign of either cluelessness or insanity. I just hope they aren’t also paying for VMware.

Pricing is a bit opaque, despite their affirmation to be transparent, but the calculator produces prices somewhere between two and five times more expensive than the competition. All cloud providers are able to cut special deals with significant discounts, so real costs may vary. It’s certainly a different strategy than their retail one, where affordability is paramount.

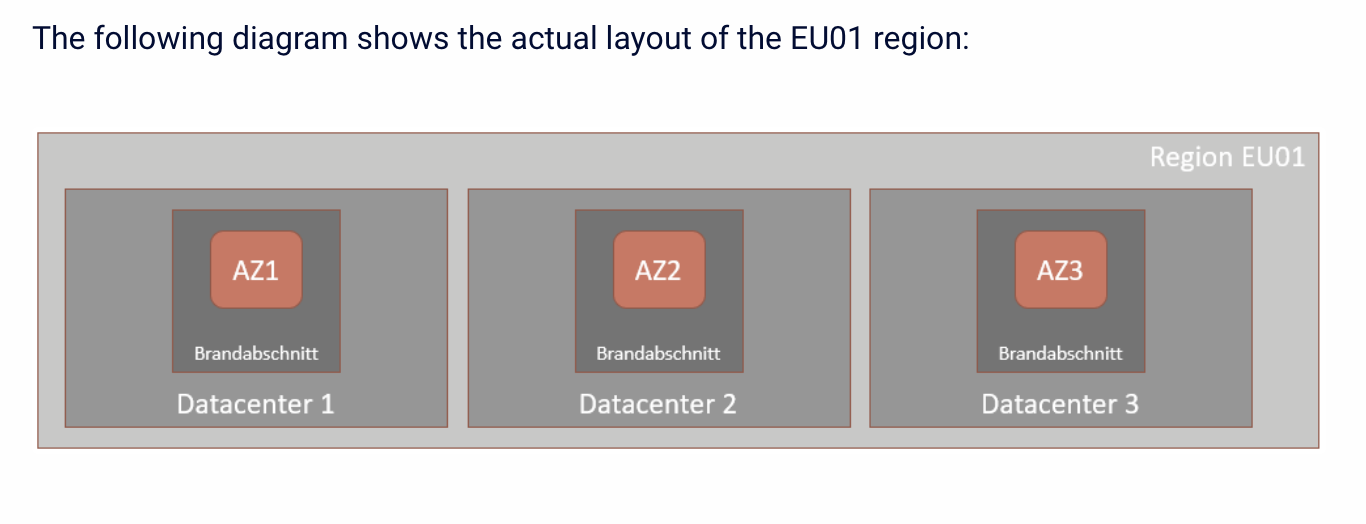

The operational side doesn’t impress either. They currently have one region: “Heilbronn/Deutschland” or “eu01”, as their documentation likes to call it. They claim it consists of at least three availability zones (AZs), but then backtrack and say that the one region they operate has exactly three AZs.

Screenshot from STACKIT docs

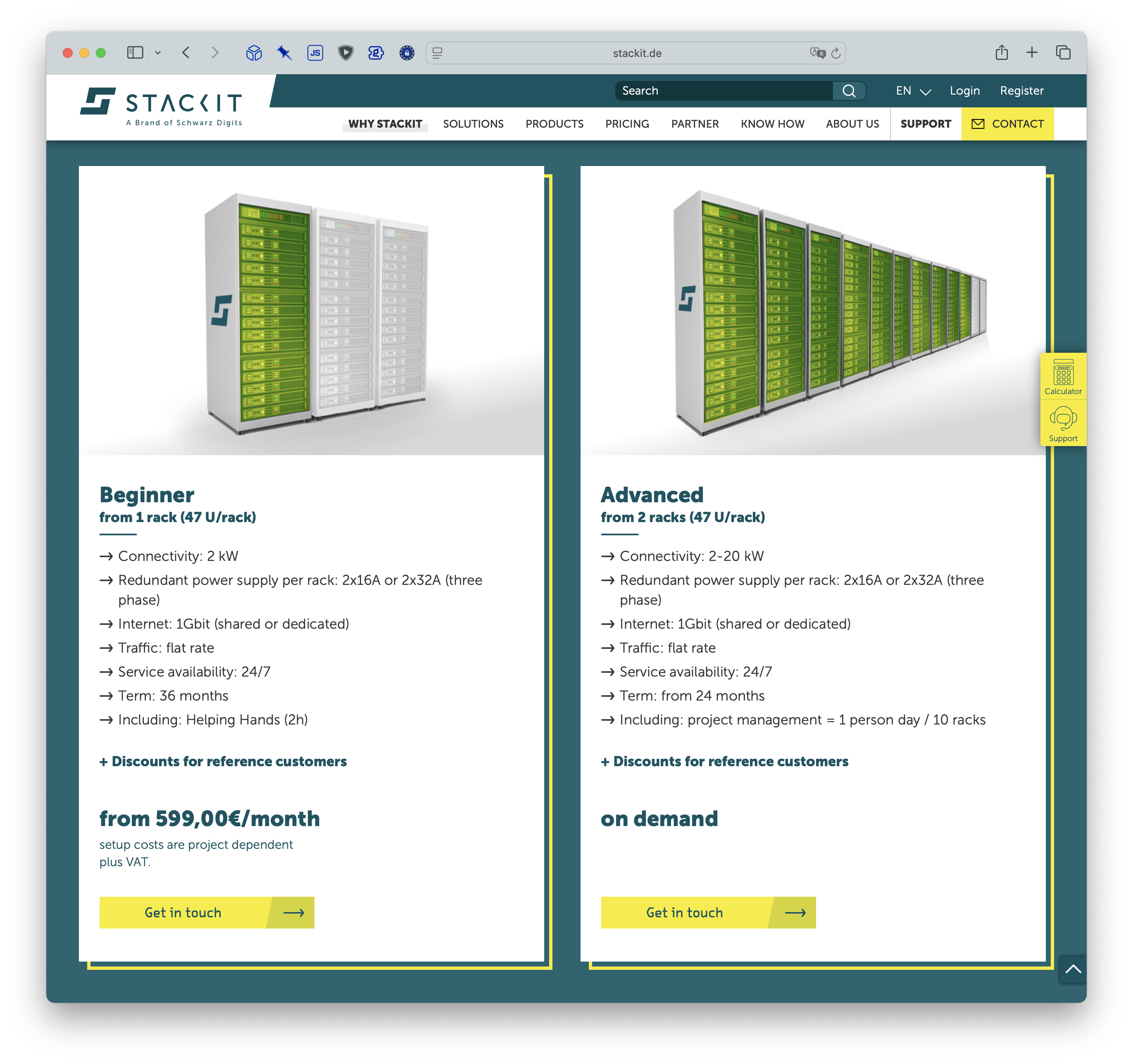

Network and power look disappointing too: while Meta, AWS, and Google started building their own network gear ages ago, STACKIT doesn’t even seem to fully support IPv6. Their colocation offer hints at a very old-school 19-inch rack setup with a pitiful 2 kW supply for 47U. At least you get a three-year contract, that’s a good thing, right?

I am cherry-picking here, obviously, but the colocation market in Germany is fiercely competitive.

Still interested? You can’t just sign up and get going: you have to apply for an account in true bureaucratic fashion. If you’re outside of the German-speaking part of the world, you will be subject to extended interrogation. Even if you sign up with a valid VAT ID, your account creation will have to be manually approved first. Mine is still pending. (Update: My account application got rejected after they asked me to submit a credit report from my bank. I am worthy enough to have credit cards or finance a house, but not to open a public cloud account.)

I’m sure the next generation of developers will patiently wait to incorporate a company and wait for your confirmation email, instead of using Google Cloud’s free tier.

Screenshot from LinkedIn

In late 2024, they hired the former managing director of Google Cloud Germany to become the CEO of STACKIT. In a LinkedIn post, he described STACKIT as a “sovereign European hyperscaler”. Their “About Us” page, on the other hand, adds “Swabian”2 and “German” to their labels. As if wrapping yourself in one flag wouldn’t suffice, they wrap themselves in multiple.

I wish them all the best, honestly. They run open source infrastructure to some extent and have opened up what could otherwise just have been an internal project. But the total lack of depth and the marketing focus on some self-defined sovereignty seems like a total miss. A narrative often presented in Germany is that Americans can advertise themselves very well without substance. I must say that some people in Germany could accidentally become number one in that regard.

It’s not 2002 anymore. There is plenty of competition on the market, some of it EU-based (EU regions of any public cloud), truly European (e.g., OVH), or German (e.g., Hetzner). There are more batteries-included solutions too (e.g., Fly.io). And increasingly, on-prem: with ever-larger cloud bills and the realization that owning instead of renting can be significantly cheaper, it will not be an easy battle for those who lack ambition.

I think a major strategic advantage of the big public cloud providers is (billing) integration: not even a vigilant CFO will mind a 20 Euro line item on a cloud bill, while an invoice from a better or cheaper new vendor may raise questions. Joining the cloud market requires a gigantic amount of capital: you need the bones, like VMs and storage, but you also need enough higher-stack services to satisfy the needs of a large number of customers. I think that Fly.io took the smarter route by partnering with select providers of high-value services, like Tigris or Upstash, while centralizing billing. Fly.io also own their hardware, but not their data centers.3

If you don’t compete on variety, depth, or value, what’s left is to be proud of your heritage. If someone on my street started offering lukewarm, stale beer for 10 Euro, I wouldn’t be proud, I would experience Fremdscham.

https://www.rhein-erft-kreis.de/aktuelles/meldungen/2024-Hyperscaler-Ansiedlung-in-Bedburg-und-Bergheim.php ↩︎

Swabia is a region in southern Germany, probably most famous for an unintelligible accent and penny-pinching abilities. ↩︎

They can still build data centers later, if they get wildly successful, since they own so much of their own stack. ↩︎